72°F (22°C) might be the norm, but it’s not the ideal indoor temperature in winter. Here’s why that number is misleading. Temperature may seem like a theoretical topic, but there’s a real, practical takeaway. Comfort matters: what good is a well designed space if you’re still freezing?

Research consistently indicates that women are more likely to express dissatisfaction indoors, when temperatures fall outside of their comfort range. Overcooling is common in offices and some homes and is a significant source of discomfort for women.

Welcome to 2025—where thermal inequity is a real term, used to describe how certain populations are disproportionately exposed to extreme temperatures. Thermal inequity shows up in everyday life too—like how women are expected to tolerate cold indoor environments designed around male comfort.

But how did we get here? The answer lies in a 1960s equation that still shapes our buildings today.

The Origins of Comfortable Temperature

In the 1960s, scientists began seriously studying thermal comfort. One of the most important researchers was Povl Ole Fanger, who didn't just measure physical factors like temperature or humidity—he asked people how they actually felt in those conditions.

Fanger developed what's now known as the Fanger Comfort Equation to quantify "thermal comfort" in indoor spaces, which became foundational in HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning) design. But here's the problem: his model was based on 40-year-old men in full business suits at a desk job. Women weren't even part of the data. Fanger also designed the model for air-conditioned spaces, but it's been used far more broadly, in ways he never intended.

This foundation explains much of today's thermal discomfort, but the issues run deeper.

Why Women Feel Colder: The Science Behind the Shiver

Metabolic Rate and Body Composition

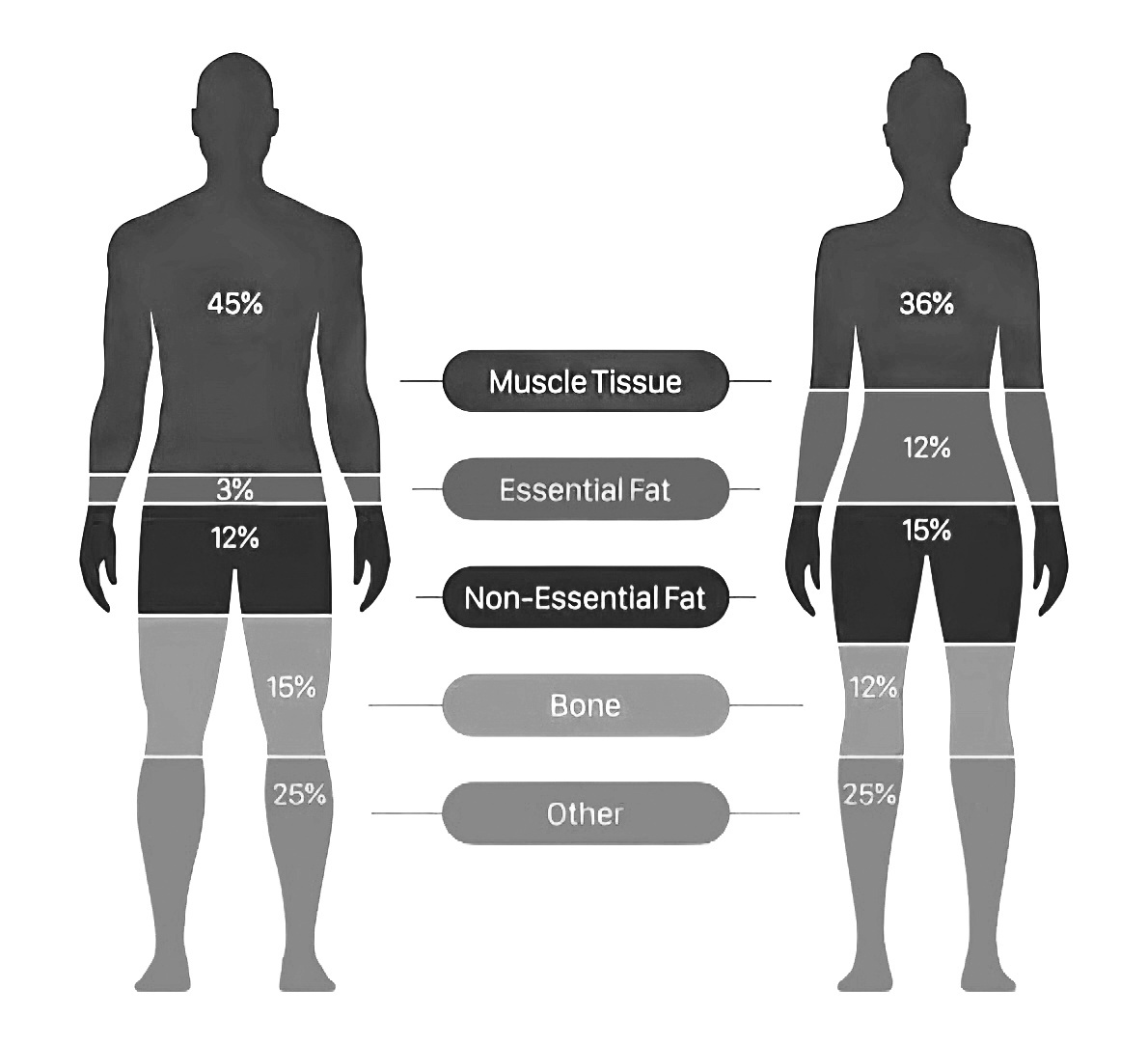

Women generally have a lower metabolic rate than men, producing less heat at a resting state. This is primarily due to having less muscle mass, as muscle generates more heat than fat.

Women tend to have more subcutaneous fat, which insulates the core and maintains internal warmth. But this can reduce blood flow to the skin and extremities, resulting in colder hands and feet even if their core temperature is higher than men's.

Size Matters

Women are typically smaller with a higher surface area-to-volume ratio, leading to faster heat loss through the skin. Polar bears don’t have this problem.

The Hormone Factor

Hormones significantly affect body temperature regulation in women:

Estrogen dilates blood vessels in the extremities, increasing heat loss.

Progesterone constricts these vessels, reducing blood flow and making extremities feel cooler.

During the menstrual cycle and menopause, hormonal fluctuations can make women feel warmer, particularly in warm environments adding another layer of complexity.

These biological differences translate into measurably different comfort zones.

The Comfort Gap: Numbers Don't Lie

Studies reveal women are more sensitive to skin temperature drops and often feel uncomfortable at lower room temperatures compared to men. The data is striking:

Men may be comfortable at around 72°F (22°C)

Women often prefer closer to 77°F (25°C)

Additionally, women's skin, especially on the hands and feet, is typically several degrees cooler than men's, contributing to the common sensation of feeling "colder," even if their core temperature is the same or higher.

But temperature isn't the whole story, environmental factors compound these differences.

Beyond the Thermostat: Environmental Factors

Temperature Preferences: Women generally favor warmer indoor temperatures—around 75.5–77°F (24–25°C), while men prefer slightly cooler settings, around 72–74°F (22–23°C).

Humidity Levels: Both temperature and humidity influence comfort. The ideal humidity range is 40–60%. Women may be more sensitive to humidity variations; high humidity can make warm temperatures feel hotter, while low humidity can intensify coolness.

Heat Distribution and Drafts: Drafts and uneven heating create cold spots that women, being more sensitive to cool air and fluctuations, often notice more than men. Inconsistent heating or cooling, especially in larger or open-plan spaces, can lead to uncomfortable cold areas even when the thermostat shows a comfortable temperature.

These challenges became personal battles as climate control moved into homes.

Home climate has a heated history

As central air became common post-WWII, the home thermostat became a symbol of control. Usually the man of the house adjusted it, and couples began arguing over temperature settings; arguments that showed up in comics, advice columns, and advertising.

Since the 1960s, thermal comfort standards have been baked into building codes, still relying on inadequate models like Fanger's. While newer adaptive comfort standards account for broader conditions, they're still not the norm—especially in office buildings, schools, and other shared spaces. Even our jokes and cultural references give it away.

"Just Put On a Sweater"

Historically, energy-saving efforts have pushed individuals to simply accept colder indoor temperatures as their responsibility. Governments told people to turn down thermostats during crises, expecting everyone to adapt to a one-size-fits-all baseline. Women felt more uncomfortable, but this was rarely acknowledged or addressed. Instead, people were told to "just put on a sweater."

In 1977, President Jimmy Carter appeared on TV in a cardigan asking Americans to turn down the thermostat to 65°F which was three degrees lower than the temperature President Nixon had requested during an oil shortage three years prior. (To quote my father, we always knew Nixon’s numbers were suspect.) In any case, the message was clear: adapt to the cold.

Even the U.S. Department of Energy recommends setting your thermostat to 68°F (20°C) in winter when you're home and awake, and 78°F (25.5°C) in summer based on averages and prioritizing efficiency rathe than comfort.

Rewriting the Rules of Comfort

Today, there's growing awareness of thermal inequity, a term used in both gender and climate justice contexts. It highlights how different groups—women, older adults, low-income communities—often experience more discomfort, higher energy costs, or worse health outcomes due to poor design of indoor environments.

Smart thermostats like Nest now let you set different temperatures and automatically adjust based on daily routines. The irony is that most people still default to those outdated "standard" settings from decades ago.

Comfort shouldn't be one-size-fits-all. Maybe we just need to add a scent to forget our problems.

The Monsanto House of the Future (1957-1967 at Disneyland) showcased futuristic home technologies, and had thermostats that could dispense scents like pine and sea.

❤️

If you found this post fun or helpful, give it a like — I’d love to know it resonated with you!

Queen’s Repository

A typical thermostat only measures temperature only where it's installed, so it might heat or cool your whole home based on just that one spot. But homes don’t heat evenly. Sunlight, room size, and insulation can all make certain areas warmer or cooler.

What’s the latest with thermostats?

Some temperature issues can be resolved through some of the newer thermostats that come with sensors.

Nest has a sensor that goes in a room so that the thermostat can use that room’s temperature to decide when to turn the heat or AC on That works well if you're mostly in one space at a time, but it’s not ideal for balancing temperatures across multiple rooms. Systems like Ecobee can average temps from multiple sensors, which gives a more even comfort level across your whole home.

This is so cool! (Oops, I did a pun!) I’m gonna save this for my students. I’m delighted that you wrote a whole essay on this subject and didn’t once mention the psychrometric chart. Yay! Mini-split systems may be a good way to enable room by room differences in heating and cooling, since each has its own thermostat. But they are costly.

Mr Fanger! say no more. Great photo. That alone kept me reading. And great cartoons. All of this was interesting - and - without knowing about Mr. Fanger, I still always knew temperature settings had to be *must be* set to a man's standard while wearing a suit. Now that suits are largely outdated, I wonder if the temperature setting has changed a bit (in favor of what a woman thinks is warm). How I remember the days of a small heater under my desk or wearing fingerless gloves. ugh.

Congrats on making the Top 100 Rising list!!! You deserve it. Your posts are always so well researched and written. Cheers!