Even though this topic has been covered widely, it’s still hard to understand the multiple architectural styles and to decipher all the jargon (for example, what is a six-over-six window?). I wanted to write the post that simplifies this and shows the differences clearly. I've categorized the styles into a smaller list since there are mainly four significant eras up to 1901.

What are row houses and where did they originate?

A rowhouse (or townhouse) is a house that takes up the width of its plot and is part of an identical group of houses with shared walls. The style was created in northern Europe and England in the 16th and 17th centuries to meet the housing needs of rapidly expanding cities. Row houses are less expensive to build and maintain because they are consistent, use repeating layouts, have shared walls, and therefore fewer windows.

The row house in New York is unique compared to row houses in other parts of the country. Although architects and builders sometimes combined and used components from several styles, there were generally four stylistic eras up until the end of the Victorian period.

The Federal Style (1790–1835)*

The Greek Revival Style (1830–1850)

The Italianate Style (1840–1870)

The Eclectic Styles of the Victorian Era (1870–1901)

* Dates are approximate, as there isn’t always scholarly consistency. 1840-60 also saw a short period of Gothic Revival.

The Federal Style (1790-1835) is spare, classical and clever.

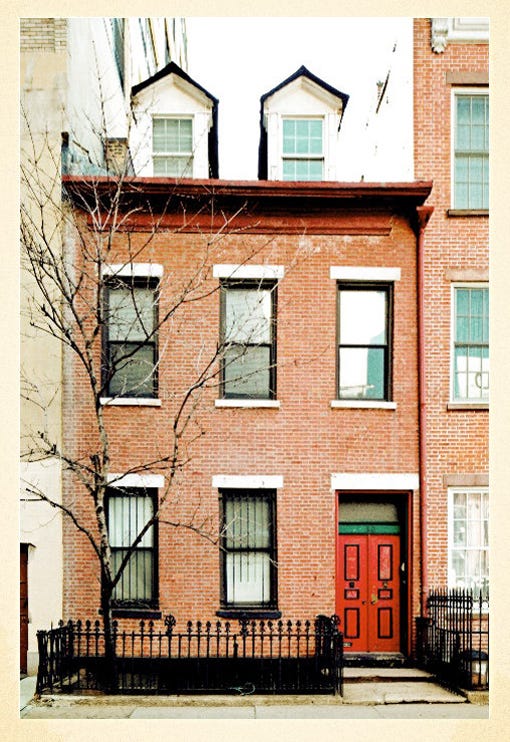

The 32 Dominick Street House is one of twelve federal houses that were built on the street. Only four are left today. It is an excellent example of Federal architecture, as it retains most of its original form and features. The windows and the steps leading to the front door are not original, but the dormers are original and seem to have stylistically correct windows.

Some of the oldest row houses in New York City were built in this style, and there aren't many left. Unlike larger standalone Federal buildings, which are blocky and massive, the Federal row house is understated and elegant. Facades are balanced and symmetrical, with a six- or eight-paneled door being the focal point. It’s a unique style because the composition and the materials themselves are used to create the decoration. This design element is seen in the window patterning, the horn-like dormers (triangular roof with pitched sides), the bare stone lintels and window sills, and the Flemish brickwork1 (see Repository at the end). Despite the spareness of the exterior, the interiors were opulent and rich, featuring plaster, classical motifs and luxurious furnishings—a clever contrast.

Origin: The style is a refinement of the Georgian style, derived from the reigns of King George I–IV, which took inspiration from classical Greece and Rome. Often known as the Adam style, it was popularized by Robert Adam (1728–1792), Great Britain’s most popular architect at the time. The ornament is typically delicate and is in the form of garlands, urns, swags, and sometimes quoins, all of which continued to be used over the course of the century. (see Repository).

Identifying features: 2-3 stories; generally 2.5 with dormers.

Facades and stoop: both clapboard and brick, with stone or wood in window sills and lintels. Stoops are usually low.

Doors and Windows: six-over-six windows (six panes of glass on the upper sash and six panes on the lower sash) with visible lintels and half-story dormer windows. The doors are six- or eight-paneled with transoms and sidelights.

Roof: metal or peaked wood cornice decorated with modillions, dentils (a small repeating block), and small brackets.

Dating a Federal House: Flemish bond was the primary brick arrangement used until 1835, so it’s one way to date a building. Another giveaway are pitched and gambrel roofs and paneled lintels made of brownstone or marble. Early federal houses will have an English basement, and later ones will have a half basement.

Greek Revival, (1830-1850) is an austere, classically derived style that took on a distinct form in America.

Like the Federal style, the Greek Revival style is derived from classical ideas. It is refined, more ornamental, and less flat than the Federal style. Columns typically form the imposing temple fronts of large Federal mansions or business buildings, but in a row house, these features are contained within entryways and porches. Democracy over individual expression was emphasized, and the repetition of form enabled the stately streetscape. The Romans served as the inspiration for earlier structures until architects opted to look even further back to the Greeks since they originally influenced the Romans.

The use of locally accessible and affordable brownstone for the base is a notable departure from the Federal era. The Greek Revival era saw a return to classical columns in all orders, (see Repository) which laid the groundwork for the taller parlor floor that emerged at this time. The houses have straightforward exteriors and interiors, with minimal embellishment in stone, plaster, and iron work. The palmette, the acanthus, and the anthemion were a few of the often employed decorative motifs. Oval or circular decorative reliefs called patera are also common.

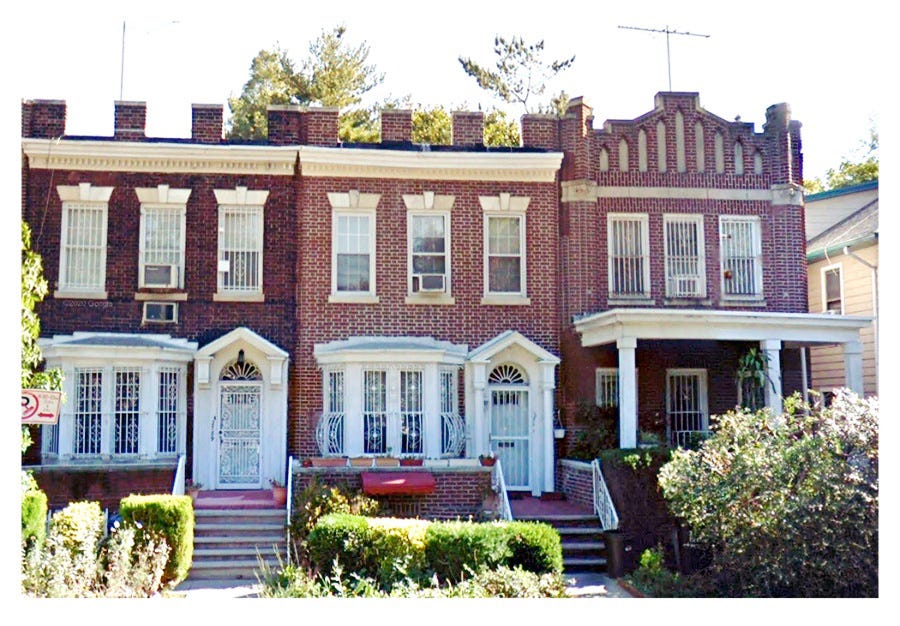

71 Vanderbilt Ave. c. 1849 is a lovely Greek Revival building with an Italianate porch that is part of the Wallabout Historic District due to it’s proximity to Wallabout Bay (next to the Brooklyn Navy Yard). It is considered a vernacular style because it was not built by an architect. It features a Greek Revival full width porch with a columned entryway that has side lights and transom windows.The entrance is original but the porch has been replaced according to the Landmarks Commission.

Origin: America’s separation from England and a wave of democratic ideals saw a return to the earliest known democracies of Greece and Rome which materialized in the form of a new American style.

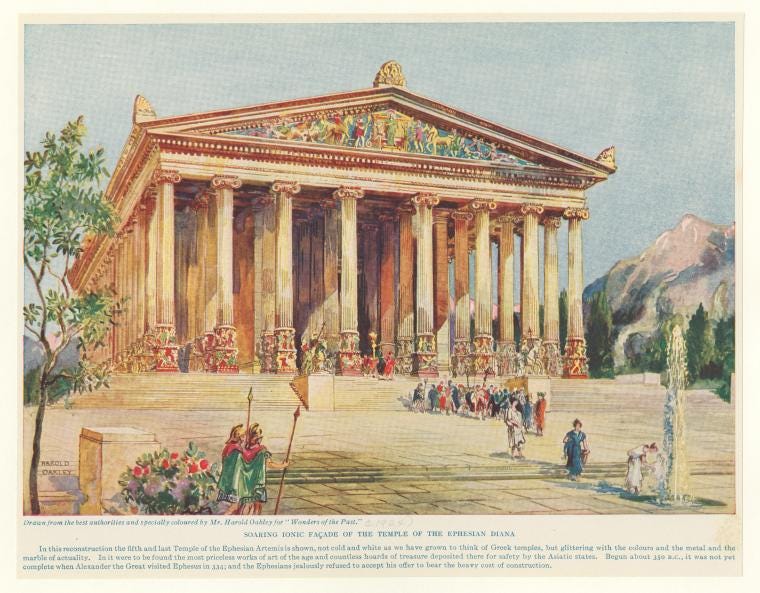

Identifying features: 3–3 1/2 stories with a basement. Houses have a grand doorway with columns or pilasters that hold up an entablature (a horizontal band with ornament). The columns were painted white to resemble Greek temples because architects at the time were unaware that these temples weren’t originally white (see Repository). Greek motifs are used both on the exterior and interior.

Facades & Stoop: unlike some later iterations that were completely brownstone, most of these houses feature a brownstone base with a brick upper façade. Siding and clapboard were also widely used. Some homes had front porches that were the entire building width, supported by Grecian columns, and decorated with Greek symbols. At this time, decorative iron balconies and porches were also common. The brickwork is in English bond (alternate rows of bricks lengthwise and crosswise).

Doors and Windows: the front doors now have longer panels and are positioned further back. The door framing is grander with pilasters or columns and side lights. The double-hung wood windows are six-over-six on upper floors and and six-over-nine on the taller parlor floor. The interior sliding pocket door was introduced at this time.

Roof: these have simple dentiled or modillioned wooden cornices that now included small windows in place of dormers.

Dating a Greek Revival house: they can be identified by their typical brownstone base and brick exterior. Plaster interiors, fireplaces, and railings all feature Greek designs.

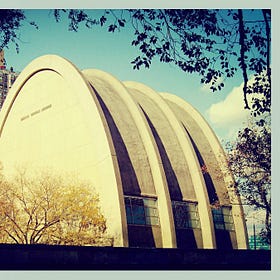

The Gothic Revival Style, 1840–1860, was a brief interlude into medievalism, an exercise in glass, steel, and ornamented stone.

The Gothic style arose out of a reaction against classicism, but it wasn't widespread. In row houses, the Gothic elements are mostly restricted to facades through the use of rough-cut stone and other decorative elements, including crenels (see Repository). Buildings are usually three stories plus a basement, either brick or brownstone. Doors are paneled and have arches with Gothic carved patterns such as trefoils and quatrefoils. Windows have decorative hoods. The use of ornamental cast iron continued.

The Italianate Style (1840-1870) produced an elegant repeatable form with some over the top decoration.

The Treadwell Farm Historic District is a small historic district located on East 61st and East 62nd Streets on the Upper East Side. Most of the buildings are four-story row houses built between 1868 and 1875. Some of them were altered in the early part of the 1900s, and stoops and the traditional ornaments were removed. The brownstone on the left is missing its stoop, and the house to its right is missing the decorative elements.

The Italianate style is regular, with uniformity created through the use of brownstone. The entry usually consists of a raised stoop with heavily decorated door and window details. A hallmark of this style are the heavy brackets with acanthus leaves and other organic forms that can border on extravagant and grotesque.

Origin: Romanticism and a rejection of classicism led to the Italian style, an unusual cross between a palazzo and a villa.

Identifying features: tall first floor known as the parlor evokes the Italian piano nobile, or noble floor so you don’t have to smell the odors or weed from the street (see Repository.) Large ornamental brackets are used for doorways and roofs. Window sills and lintels are heavy and project outwards.

Facades and Stoop: facades are 2-4 stories with a brownstone basement. There is heavy ornamentation around doors and windows. The high stoop is common and has ornate cast iron rails, newel posts, and balusters.

Doors and Windows: entry doors are double doors, usually quite heavy with curved tops. Doors are deeply recessed, and the framing has columns and brackets with carvings, but columns were mainly for the rich. Windows are tall and narrow, usually double-hung, two-over-two, or one-over-one.

Roof: these are low-pitched or flat with a heavy cornice, overhanging eaves, and substantial brackets.

Dating an Italianate house: brownstone with bulky cornice that has heavy brackets and projecting eaves Fantastically stylized organic forms like acanthus leaves.

The Eclectic Styles of the Victorian era (1870-1900) were many and varied but classicism never left.

The Second Empire (1860–1875) is a Victorian evolution of the Italianate style.

The feature that uniquely identifies this style is a mansard roof, usually made of slate shingles in polychrome patterns. The roof is a visual illusion, as it makes a full story look like only half from the outside. Buildings in this style are 3-5 stories with a wide stoop and ironwork similar to Italianate buildings. A Second Empire brownstone closely resembles the Italianate style, but some of these houses also incorporate Neo-Grec or Greek Revival ornaments and porches.

The Neo-Grec style (1865–1885) is flat with delicate carvings and reliefs.

It is characterized by classic, stylized and angular details, often incised into brownstone. Brick and stone are sometimes artfully mixed, and sometimes there will be a group of houses painted in different colors. Generally, buildings are 3-5 stories high and can be either brick or brownstone. Like Italianate houses, the doors are heavy and angled, with incised details around the doorway that also extend to the windows. Windows are two-over-two or one-over-one. Cornices are heavy, bracketed, and project outwards.

Queen Anne (1870–1899) is an eclectic hodgepodge of styles that somehow worked.

The style is a mix of Romanesque, Classical, and Renaissance. The vertical façades are characterized by asymmetry and usually contain bay windows. The style features an elaborate array of colors, materials, and textural elements that seem to coagulate, devoid of any historical precedents in form or proportion. Windows and doors vary in size, and stained glass is sometimes used in the top sash. Roofs are gabled, with slate and terracotta, and often have dormer windows.

The Romanesque Revival (1880–1890s) is massy and textural and incorporates bizarre decorative elements.

The style, a marriage of 11th-century Romanesque with Queen Anne, is heavy due to its use of varied materials, including granite, limestone, brownstone, colored bricks, and terracotta. The base of the buildings is usually heavy stone that projects out a few inches. Columns and pilasters are short and may not follow the Greek orders. The facades are richly ornamented with carvings of foliage, human and animal heads, mythical beasts, and scrolls. It’s sometimes not pretty when you get up close. Decorative arches are common with keystones. Doors are double, paneled, and very recessed in round archways. Windows are usually one-over-one and vary in size.

The Renaissance Revival (1880–1920) is a simple and subtle nod to classicism.

The houses are 2-3 stories high with a basement and are characterized by L-shaped stoops. Classical ornaments of wreaths, fruit, and flowers adorn doors, windows, and the cornice. Houses may have wrought-iron balconies and formal entryways. Doors are wood double-leaf doors with glazed openings and may have ornamental iron.

The Colonial Revival (1880–1930) harkens back to early American colonial buildings.

Because it draws inspiration from early American architecture, it shares many characteristics with the Greek and Federal styles. The houses are usually brick in Flemish bond with a high stoop and simple steps. Doors are six- or eight-paneled, very similar to the Federal style. Windows are multi-paned and double-hung. Simple iron handrails and fences are on the outside. Details such as urns, festoons, and broken pediments are visible. Roofs are simple and have a dentilled cornice.

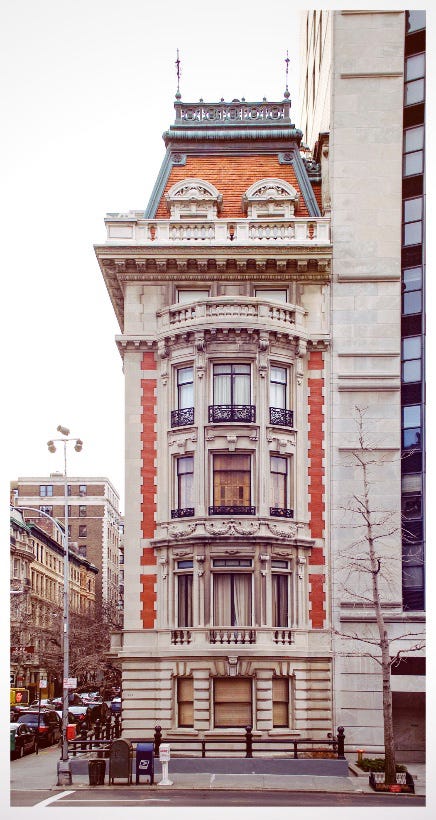

The Beaux-Arts style of 1890–1920 is sophisticated, stunning, and bold.

These are imposing structures, usually five stories high, and they are highly planned and sophisticated built with marble, limestone, or light brick. Beaux-Arts buildings have bold, projecting ornament in the form of swags, cartouches and garlands. Facades are classical, with an emphasis on symmetry and uniformity. The main floor is a level higher than the street and typically grand, with larger windows and balconies. Iron work is heavily patterned and used throughout the facade, especially on balconies. Windows are double-hung and casement, and you’ll see curved trim, particularly on bay windows. Cornices are sheet metal with brackets that are embellished with friezes.

If you like this post, please share or heart. If you like Architecture, please follow my Instagram.

Related content:

In New York City, the Chances Are High That You Live Close to a Landmark

(Paid post) Perhaps you live in a landmarked building or have walked by one without knowing it. Today, historic preservation isn’t just about old buildings and has grown to encompass a broader range of built environments including those that have social and cultural significance. Landmarks capture the changing face of our city; imprints of transformation across time.

Get Plastered

(Paid post) Historical plaster has significance and tradition. It’s important to have an understanding of the advantages and disadvantages to make sound decisions.

Queen’s Repository

References

Landmarks Preservation Council: Row House Manual (PDF)

Glossary

Bracket

A bracket is an element that protrudes from a wall or surface and supports weight.

Cartouche

An oval shape or shield usually containing an inscription or date, frequently set in an elaborate scroll frame and bordered with ornament.

Clapboard

Clapboard is one type of siding made of long, thin planks of wood used to cover houses. Nowadays most siding is out of vinyl.

Historic siding can be sourced at Davis and Hawn.

Corbels

The are projecting elements as deep as they are wide. Brackets on the other hand are usually deeper than they are wide. Corbels are usually more ornate as well.

Cornice

A cornice is a decorative element that caps a wall or an architectural structure.

Federal-style cornices feature medallions, dentils and small brackets. Modillions are horizontal brackets (smaller than corbels) directly below the cornice. They can be shaped like a block or an element like an acanthus leaf, etc. A dentil is a tooth-like repeating block in the bed mold (the molding that covers the area where the wall meets the ceiling). Brackets are decorative but also hold the cornice in place.

The Italianate cornice features very heavy brackets, larger decorative elements and projects outwards.

Crenel

Crenels are gaps that occur at regular intervals along a parapet.

Eave

The underside of the part of the roof that projects beyond the exterior wall.

English basement

An English basement is a high basement that is mainly above ground and often just means the lowest level. It is often referred to as the garden floor.

A half basement or semi-basement is half below ground, rather than entirely such as a true basement or cellar.

English bond

Brickwork laid in alternating courses of headers and stretchers

Entablature (Greek Revival)

An entablature, is a horizontal band with molding supported by columns.

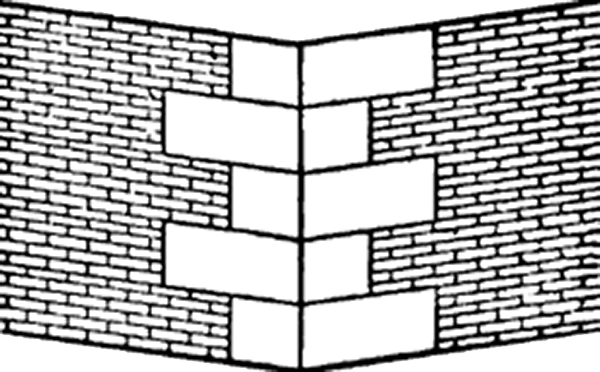

Flemish Bond (Federal)

The Flemish bond (see Footnotes) didn’t originate in Flanders or nearby France or Holland but had been used in central and northern Europe. It was seen in England in the 1600s but popularized only 200 years later.

Below is an illustration of Flemish bond in a 8"-thick wall Every alternate brick is a header laid perpendicular to the stretcher. Corners use a 3/4 brick. Bricks alternate in placement in each row.

Festoon/Swag

A string or garland of flowers, fruit or foliage tied with ribbons in the middle and draped between two supports

Garland

A wreath or festoon of flowers, leaves, or other material

Greek Temples and Orders (Greek Revival)

The temples of Ancient Greece were brightly colored but Greek Revival architects were unaware so they made everything white. The Doric Order is the oldest and simplest and was the most commonly used order in Greek Revival buildings.

Patera (Greek Revival)

An ornament that is shaped like a shallow dish that was used for drinking in ancient Rome. It is usually circular or oval with petals or leaves.

Pediment (Greek Revival)

A triangle shaped crown over an opening.

Piano nobile

The Italian term refers to the noble level refers to the floor of a palazzo generally thought to have better views and would be less damp and smelly because it wasn’t at street level.

Quoins

Masonry blocks placed at the corners of walls sometimes to provide strength when the wall is made with inferior materials.

Footnotes

Gratias Roman: A primer on Northern European Brick. Jeevan Panesar, 2018 traces the origin of Flemish brickwork.

I found that absolutely fascinating. What a great read!

Great breakdown and illustrations!